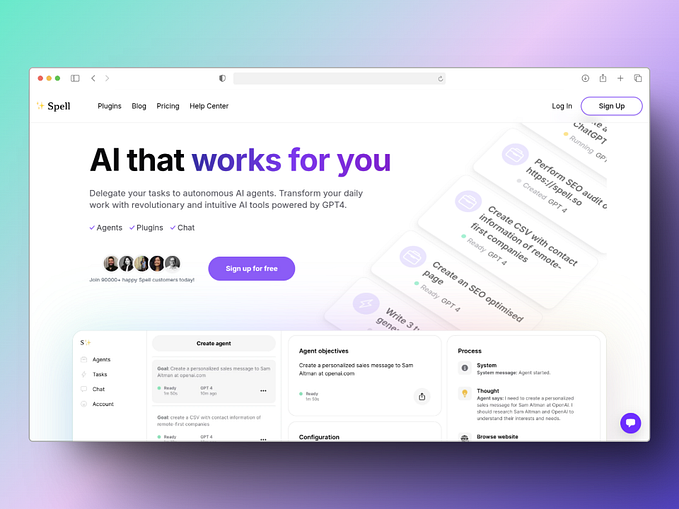

Technology — AI, creativity and angry humans

Recently I innocently posted online (OK, maybe not so innocently) a few graphic images from a hot and hip open-source AI image generator called Stable Diffusion 2. The reason for this was an ongoing debate I have had for years with an architect friend of mine. My position is that AI will eventually (in our lifetimes) compete successfully with human creativity in essentially every conceivable field.

My architect friend, and most people, do not agree. Vociferously so.

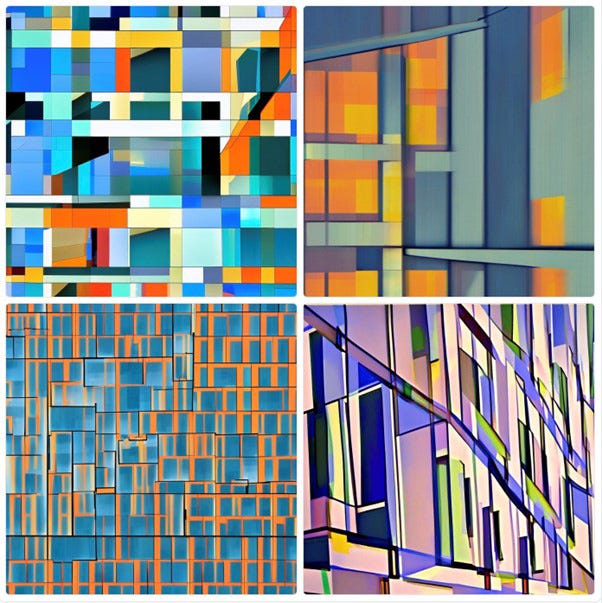

I wanted to show my friend that the AI could create a pleasing, surprising and imaginative graphic for the cover of a hypothetical book on modern architecture, or perhaps a banner ad for an architecture conference.

So I typed the following into the text box on the front page of the Stable Diffusion 2 website — ‘architect imagination, building with clean lines, impressionist’

It produced 4 images in 60 seconds. Here they are:

.

The bottom right image, at least for this beholder, is beautiful, unusual, imaginative, apt. Had it been designed by a human artist I would have been just as impressed.

My post on Facebook ruffled many feathers. Objecting contributors (all friends) were deeply offended (or highly skeptical, at least) by the prospect of an AI out-creating a human. Their outrage rose hot from the screen. It felt to me like a sort of anthropomorphic arrogance, in which it was assumed that no machine ever would be able to match the creative output of an artistically talented human.

The word ‘soulless’ was used a lot, although I am not sure who gets to be the authority on that.

I find it impossible to accept this position. Why? Because we too are simply machines, a little wetter than computers perhaps, but bundles of chemicals nevertheless. At least for non-religious types like me. Why couldn’t other types of machines outlearn, outthink, out-create us? In which way are we more special?

Some of my adversaries on my post complained about the image produced by Stable Diffusion 2 being merely an assembly/aggregation of many stored images with some cheap tricks thrown in. This is not even vaguely accurate. The program is a result of many man-years of work by both artists and computer scientists who sought to understood what an artist actually did when faced with a creative problem or project.

Inferences, connections, access to truly staggering amounts of visual references, English understanding, history of art, networked entanglements, noise pruning, emergent properties. There is so much intelligence and creativity and (most importantly) unpredictability bundled into this system that it is apparently difficult to retrace the ‘thought process’ that led to the image creation.

I have written a few novels. I typed in the titles of the novel and a one sentence description of the theme of the story. The book covers that emerged were startling and wonderful. And in some cases, far more interesting that than some of the covers designed by the publisher’s graphic designers. Which, given my friendships with people in the field of graphic design, is very scary indeed.

Artificial intelligence — the search to reduce human intelligence (and by extension creativity) to code and algorithms has been with us for many decades, ranging back to people like Marvin Minsky at MIT in the 1960s. It has existed in the shadows for a long time, making little progress, overpromising and underdelivering.

But the perfect convergence of dizzying and accessible compute power, cheap storage and the emerging mathematical disciplines of neural networks and machine learning has suddenly shoved AI into the limelight over the past 10 years.

For instance, not too long ago many anthropo-centrics claimed that machines would never beat a human at chess or the much more difficult game of Go, considered to be the most complex board game ever invented. At the highest levels of gamesmanship, these were thought to be the domain of creative intellectual genius for hundreds of years.

It turns out they weren’t so special. The world’s greatest Go master, Lee De-Sol swore never to play again after losing to Meta’s AlphaGo some years back. And chess got conquered by machines a long time ago.

AlphaGo’s successor. AlphaGo Zero taught itself to the best Go player in the world in about 48 hours from a standing start. It did not ‘brute force’ its approach to the game by learning from historical games, as had previous versions. It learned by playing against itself hundreds of millions of times and developing strategies along the way that humans had never thought of.

Which brings me Ian S. Thomas. He is a multitalented, multigenre South African creative, recently decamped to the US with his family. I have met him a couple times over the years, usually in social settings. I knew he was in the advertising business, but one afternoon over lunch I found out that he wrote poetry too (among other things).

And then I found out that one of his many books of poetry, entitled I Wrote This For You, is a global #1 bestseller, having sold hundreds of thousands of copies. I have never heard of a poetry book selling that many copies. Quoted by Steven Spielberg and Arianna Huffington, fan-boyed by Harry Styles and Camilla Cabello and his poetry read to the Royal family in London. It turns out that Iain is somewhat of a media superstar.

Anyway, he has co-written a new book called What Makes Us Human. 95% of the book was written by a natural language AI called GPT-3, a fact of which he is happily proud. The other 5% was written by Iain and one of his co-writers, Jasmine Wang. The third co-writer credited on the cover is…GPT-3. The reviews are glowing.

People are not particularly exercised by AI when it is applied to voice recognition products like Siri or X-ray diagnostics or self-driving vehicles or intelligent automation of all manner of administrative drudgery.

But try to apply it to tasks considered to be the sole province or humans, that of creativity, and people be getting very pissed off, judging by the more colourful comments on my FB post.

I wonder why?

Steven Boykey Sidley is a Professor of Practice at JBS, University of Johannesburg.